by

Harriet Hyman Alonso

Introduction

In 1889, twenty-nine year old Jane Addams opened the doors of Hull House in the West Side of Chicago, a slum, teeming with impoverished immigrants. Here she led a group of young reformers in establishing programs to improve the neighborhood. Within four years, the settlement house boasted an array of clubs and functions, a day nursery, gymnasium, dispensary, playground, and a cooperative boarding house for single working women. By 1907, the complex had thirteen buildings and a children’s summer camp outside the city. Hull House made Jane Addams an international figure.

The following story is just one of hundreds which exemplify life and work at Hull House. It tells of the community’s belief that Addams was harboring a “Devil Baby,” an infant monster born out of sin. But as Addams soon observed, the type of wrong-doing committed depended on who told the story.

Here I present to you the story of the Devil Baby as Jane Addams understood it. I follow this with a “deeper analysis” I developed through reading the Chicago Tribune for the time of the crisis. I have ended the piece with a few questions and projects for the development of an even deeper interpretation . . . your own!

Enjoy!

The Story

On All Hallows’ Eve, October 31, 1913, an article in the Chicago Examiner screamed, “’Devil Child’ Still Sought by Thousands.” “All over the West Side in Chicago,” it stated,

the story was spreading yesterday in a score of forms. The “demon baby” was supposed to be at Hull House, where Miss Jane Addams and other residents spent the whole day denying it. One understood that the baby had horns; another that it spoke from a serpentine-shrewd brain; another that it laughed in the cynical way of a bitter old man.

“I suppose a deformed baby was born somewhere on the West Side” said Miss Addams. “That to see the way otherwise intelligent people let themselves be carried away by the ridiculous story is simply astonishing. If I gave you the names of some professional people—including clergymen—who have asked about it you simply would not believe me.”[1]

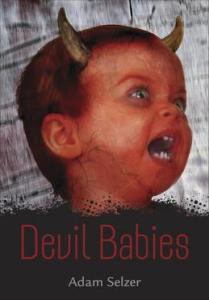

Image from http://www.theparanormalguide.com

But how did this story take hold and spread so quickly that by the end of the six-week onslaught on Hull House, thousands of people knew about it? Indeed, many of them had made a considerable effort to wend their way through the crowded streets of Chicago just to see this “Devil Baby” in person. And what did it mean to Jane Addams who, beginning in 1914, wrote about the incident a number of times? First she submitted it as a short piece for the American Journal of Sociology.[2] Then, in 1916, an article appeared in the Atlantic and the book, The Long Road of Woman’s Memory was published.[3] Finally, in 1930, Addams related the story once again in The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House.[4] Each version differed only slightly from the others, but each certainly reflected Addams’s feeling that the Devil Baby story showed “a certain aspect of life at Hull-House which nothing so adequately conveys.”[5]

The Devil Baby began its life-journey at the end of September, five weeks before the press reported it. By then, thousands of people had come in search of this tantalizing monster, word reaching them, as Addams described it, through the “old method of passing news from mouth to mouth.”[6] It was the perfect time of year for such a sojourn. Already, the exceedingly hot summer was turning into autumn, the days rapidly growing shorter and the temperatures dropping dramatically from over ninety degrees down to the fifties within days.

Colder weather often produced tension for poor people who worried about staying warm in a city with often cruel, windy, snowy winters. And this tension sometimes resulted in unusual doings. Still, it came as a surprise to Jane Addams and Hull House residents when one day three Italian women banged on the door of Hull House demanding to see the Devil Baby that they absolutely believed was being hidden there. It is easy to close your eyes and imagine how the scene played out—the women’s faces ruddy from their rush through the early autumn cool air, their eyes full of the excitement of a juicy story to pass on to their friends and relatives. All they needed was to see the baby in person so that they could add drama to their tale. Picture this:

“We want to see the Devil Baby,” they shouted at the Hull House resident who opened the door. Pushing their way inside, they looked this way and that. “Where is it?”

“What are you talking about?” the young woman asked.

“The Devil Baby. We know that it’s here.”

One woman held up two fingers to form horns on her gray head. Another held out her wrinkled hands with two fingers separated in the middle to resemble hoof-like feet. The third pointed at her crooked teeth and chomped her mouth up and down. Then she turned around and wiggled her fingers near her rear end to indicate its twitching tail.

“We’ve heard it was left here and that you’re protecting it. We need to find it and take it to the church.”

“Who told you this?”

The first woman said, “A woman at the market told us about that poor pious Italian girl who married an atheist. Such a good soul she is. Her husband, that heathen, tore a picture of the Holy Virgin off the bedroom wall because he hated to see her.”

The second elbowed the first woman aside. “Then he yelled and screamed at her that he would rather have the Devil himself in the house instead of this beautiful, sacred picture.”

The third woman pushed herself ahead of the second. Pulling her black wool shawl over her head, she leaned into the Hull House resident and added in a hushed voice, “This is the worst part. The Devil heard that wicked man’s curse and entered the soul of her coming child.”

The resident caught her breath and backed away from the woman.

“Even worse yet,” the first one said, pushing the third one away, “as soon as the Devil Baby was born, he got up on his cloven hoofs and chased his father around the kitchen table, all the while shaking his finger at him and cursing.”

The second woman took over. “After a long time, the father caught him and even though he was shaking all over in fear, he picked him up and brought him here. . . to you.”

Again the third woman came forward. “We heard that you took him to church to get baptized, but when you opened the shawl he was swaddled in, it was empty. The Devil Baby had escaped and was running over the back of the pews.”

All three asked in unison. “How did you get him back here?”[7]

Of course, the residents of Hull House were astonished by the women’s claims. They insisted that there was no such baby. But from early morning until late into the night for the next six weeks, the door-bell buzzed nonstop; the telephone rang off the hook, and lines of people stood outside Hull House demanding to come inside. Most days, it was nearly impossible to do the necessary everyday tasks or tend to the many programs scheduled to take place.

Jane Addams heard the residents standing firm.

“No, there is no such baby.”

“No, we never had it here.”

“No, he couldn’t have seen it for fifty cents.”

“We didn’t send it anywhere, because we never had it.”

“I don’t mean to say that your sister-in-law lied, but there must be some mistake.”

“There is no use getting up an excursion from Milwaukee, for there isn’t any Devil Baby at Hull House.”

“We can’t give reduced rates, because we are not exhibiting anything.”[8]

As the weeks passed, the visitors became more belligerent. Why was Jane Addams harboring this horrible monster? Why wouldn’t the residents admit that the Devil Baby existed? After all, some had traveled far distances at a time when transportation was not as easy as it became just a few years later. They were irate, to put it mildly.

“Why do you let so many people believe it, if it isn’t here?”

“We have taken three lines of cars to come and we have as much right to see it as anybody else.”

“This is a pretty big place, of course, you could hide it easy enough.”

“What are you saying that for, are you going to raise the price of admission?”[9]

Some people insisted on relating their own alternate version of the existence of the Devil Baby. Jane Addams recalled a Jewish woman who told her that “the father of six daughters had said before the birth of a seventh child that he would rather have a devil in the house than another girl, whereupon the Devil Baby promptly appeared.”[10]

In another version, a man married an innocent young woman without confessing to her or to a priest a hideous crime he had committed years before. His deception became “incarnate in his child, which, to the horror of the young and trusting mother, had been born with all the outward aspects of the devil himself.[11]

To Addams, the story reverberated like an old-wives’ tale, one of those myths that travels over time and seeks new harbors with every generation. “Save for a red automobile which occasionally figured in the story, and a stray cigar which, in some versions, the new born child snatched from his father’s lips, the tale might have been fashioned a thousand years ago,” she said.[12]

Initially, there was such a constant hub-bub that Jane Addams gave no thought to the age or gender of the visitors. In fact, she found the entire parade of gawkers revolting. But rather quickly, it dawned on her that the majority of those passing the story along were women. And older women, at that. Most were immigrants who had been ripped away from village life only to find themselves engulfed in the confusion of a huge urban center. Many worked hard at menial jobs throughout their entire lives. Too many were stressed to the point of a mental breakdown. For Addams, these older women were particularly vulnerable to the Devil Baby myth. As she later claimed,

Whenever I heard the high eager voices of old women, I was irresistibly interested and left anything I might be doing in order to listen to them. It was a very serious and genuine matter with these old women, this story so ancient and yet so contemporaneous, and they flocked to Hull-House from every direction; those I had known for many years, others I had never known, and some whom I had supposed to be long dead.[13]

Something about the mystery of the Devil Baby and its horrible consequences brought new life to old lives.

Now, Jane Addams herself was no longer what one would call a young woman, as so many of the Hull House residents were. On September 6, 1913, she turned 53. The average life expectancy for women at that time was only 55.[14] When Addams looked in a mirror, she could see the toll the years had taken on her. Her body was no longer slim; the skin on her face had begun to sag, and her hair was graying. On many days, dark shadows appeared under her sad-looking eyes as exhaustion took its toll, and her chronic back pain plagued her.

Yet, Addams was one of the most vital and optimistic women of her day. Nothing slowed her down as she worked as Vice-President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association or as Chair of the Progressive National Service Committee, paying special attention to the Social Industrial Justice Department. She traveled the world, having spent the six months before the Devil Baby incident visiting nations in Europe and the Middle East.

Perhaps when Jane Addams looked at her contemporaries in the Hull House neighborhood, they appeared older than she did. In actuality, many were close to her in age; others, much older. It was often hard to tell when poverty, constant grueling work, and lives full of disappointment and heartache had worn them down. Yet, Addams felt an affinity with them. Being “older” herself, she could identify with the deep need for these women to be in the center of something. Anything, in fact. As younger women, they had been vital to the well-being of their families and community, but as older women, they had become invisible. To most of their younger relatives, they were at best a reminder of their family history. To others, they were a burden, especially once they needed to be taken care of instead of being the care givers.

As Addams witnessed these women’s insistence on the Devil Baby’s existence and their seemingly huge investment in being involved in propagating the myth, she took note of the different effects the story played on their lives. They especially longed to feel their self-worth return, and perhaps the Devil Baby could help them do this. They certainly took great risks to see it.

One elderly woman, whose very appearance touched Addams deeply, dragged herself from her small bed in the poorhouse to come and see the Devil Baby. This was no easy feat as she had absolutely no money and was physically disabled as well. For days, she planned her escape so as not to be noticed by the poorhouse wardens.

Finally, she made her move, struggling across the street to a saloon in order to beg the ten-cent car fare from a young bartender. She promised she would pay him back, and even though he barely had enough money to survive on, he lent it to her. Then, he and the conductor lifted her into the street car.

That woman felt mighty proud of herself. Whereas at that time, poor men took off during the summer to travel the highways and byways seeking work, no self-respecting woman would consider that option. Yet, here she was breaking the traditional rules by heading off to complete a most urgent task. Being unable to do very much for herself, she was simply elated over the fact that she had escaped the poorhouse and was a paying customer on the street car.

Even though the effort made the woman feel “clean wore out,” she felt that just setting her eyes on the Devil Baby would be payment enough for all her trouble. She could then return to the poorhouse and revel in telling the other women in her ward about that baby “at least a dozen times a day.”[15]

Jane Addams’s heart opened to this feeble woman. She felt so sorry for her that she could not bring herself to immediately tell her that the Devil Baby did not exist. Instead she settled her into a comfortable chair in the Hull House parlor, served her a cup of tea, and listened intently to her story. In large part, she was doing anything to postpone revealing the truth.

In turn, the old woman told Addams that her mother, who had spent her life in Ireland, had possessed second sight. She had heard the fabled Banshee cry out three times before a poor soul was called to Heaven. She, herself, she bragged, had heard the Banshee once. She offered Addams her great expertise. Her special powers could help in interpreting the meaning of the Devil Baby’s appearance at Hull House. Addams looked at the woman’s “misshapen hands lying on her lap [that] fairly trembled with eagerness.”[16] But she knew that she had to disappoint her, and she did.

The very next day, another woman from the neighborhood called on Jane Addams. Her old, bedridden friend absolutely refused to believe there was no Devil Baby at Hull House unless “herself” came and told her in person.[17] Addams knew this woman in her younger days when she was the proprietor of a very prosperous second-hand shop. Now, because of her husband’s and sons’ alcohol abuse, the store and her menfolk were gone, leaving her alone with no money and with the care of a young grandson to boot. The Devil Baby seemed an answer to her prayers. If she could actually see the child and relate this to her neighbors, she would gain credibility, and perhaps, some charity.

Immediately after receiving the call, Addams donned her hat and coat and walked the crowded, dirty streets to see her. By this time, she felt so bad that she had almost convinced herself to concoct a description of the Devil Baby as not to bring heartbreak to another poor, unhappy woman.

“As I walked along the street and even as I went up the ramshackle outside stairway of the rear cottage and through the dark corridor to the ‘second floor back’ where she lay in her untidy bed,” Addams wrote, “I was assailed by a veritable temptation to give her a full description of the Devil Baby, which by this time I knew so accurately (for with a hundred variations to select from I could have made a monstrous infant almost worthy of his name), and also to refrain from putting too much stress on the fact that he had never been really and truly at Hull-House.”[18]

After all, what harm could there be in giving an old woman, so ill that she had but little time to live, a bit of satisfaction?

But the woman immediately saw Jane Addams’s worried face. She felt her reluctance to enter her room. Putting the signs together, she knew she was about to experience just one more disappointment in her life.

At first Addams thought that these “pitiful” older women were looking for a second chance at life, but eventually she decided this was not the case. Most of them had “little opportunity for meditation or for bodily rest.” Instead, they either had to “keep on working with their toil-worn hands, in spite of weariness or faintness of heart” or struggle through each day just trying to keep their bodies going.[19]

For some unexplainable reason, the Devil Baby gave them the confidence to relate to Addams their lifelong sufferings. As one woman explained, “It’s the foolish way all the women in our street are talking about the Devil Baby that’s loosened my tongue, more shame to me.”[20] And tongues were loosened, for sure.

Several described scenes of domestic violence. One told Addams, “My face has had this queer twist for now nearly sixty years. I was ten when it got that way, the night after I saw my father do my mother to death with his knife.”[21]

Another told her:

You might say it’s a disgrace to have your son beat you up for the sake of a bit of money you’ve earned by scrubbing—your own man is different—but I haven’t the heart to blame the boy for doing what he’s seen all his life, his father forever went wild when the drink was in him and struck me the very day of his death. The ugliness was born in the boy as the marks of the Devil was born in the poor child up-stairs.[22]

Others told of premature fetal deaths from men kicking them in the side, of their own guilt when children were maimed and burned from kitchen fires because they had no one to watch them when they went to work, of children’s deaths because husbands would not or could not spare the money for a doctor to treat a sick child.

For all of these women, the Devil Baby represented something basic. An innocent woman—like themselves—had been mistreated. Husbands and grown children had beaten, humiliated, and impoverished them. Yet, these women were the ones punished, just like the poor mother of the Devil Baby, who was a victim, not a perpetrator, of a great injustice.

However, there were ways in which a tired, forgotten older woman or an angry middle-aged one could use the Devil Baby to exert her influence and be seen as a sage. A number of older women, for example, used the Devil Baby to help out those daughters and grand-daughters who had abusive husbands. Remembering their own weary years of poverty, numerous pregnancies, neglect, and domestic violence, they pressured those younger than themselves to get their men to Hull House. Maybe witnessing the reality of the Devil Baby would scare them into decency. “Maybe seeing the Devil Baby,” Addams later wrote,

would make those who drank too much, or cursed, or abused their wives and children to stop doing so. If they didn’t, perhaps they would be responsible for bringing a Devil Baby into the world. . . What story could be better than this to secure sympathy for the mother of too many daughters and for the irritated father; the touch of mysticism, the supernatural sphere in which it was placed, would render a man quite helpless.[23]

For Jane Addams, women throughout the ages knew that myths like the Devil Baby could provide aid in shaping human relationships. In fact, in a world where men held the power, the Devil Baby offered a tool of change and control.

But what exactly did it mean to those living in poverty in 1913 Chicago to “tame” men? What was the proper behavior for married men and fathers? The answers will seem quite simple and logical to us in the twenty-first century. Being a good husband and father meant not spending a week’s pay on gambling and drinking. Instead, it meant bringing the pay envelope home to be opened by the wife. Since earnings were in the form of cash, not checks or direct deposits to banks, the first thing was to be sure the expenses for the upkeep of the family were taken out. Only then could the bread-giver claim a piece of his earnings for a drink or two with his pals at the nearby saloon.

Next, being kind and considerate were essential. Not slapping a child or hitting a wife meant peace for a home. Jane Addams witnessed the bruises on many a woman and child and made it a mission of Hull House to teach that there were better ways to end conflict, both inside and outside of the home. She also saw conflict resolution as a useful tool in bonding people of different ethnic and racial groups together and, taking it a step further, to securing international peace and justice.

In addition, for many women, a religious man was a good man as religion offered a moral code of conduct and discipline. If a man was a regular church goer, he was less likely to use his hard earned money for alcohol or gambling.

Indeed, many men did make the trip to Hull House. Some were dragged there “shamefaced” only to feel “triumph” when no Devil Baby appeared. Others came on their own, believing their mothers and wives must have seen it, and therefore, its existence was proved. They offered from twenty-five cents to two dollars to get a peek at this curiosity attraction. This was no small sum for a poor family. Addams asked one group if they really believed that a respectable institution such as Hull House would actually exhibit any “poor little deformed baby.” “Sure, why not?” they replied. “It teaches a good lesson, too.” After speaking with a number of such men, Addams became convinced that such a story as the Devil Baby could indeed work as a “restraining influence” in a marriage.[24]

The layers of meaning of the Devil Baby were numerous and complex. Jane Addams noticed that mothers often used the example of the Devil Baby to control their daughters’ behavior. It frightened them to see their girls head off to dance halls or go out walking with strange men they met on the streets. But often, girls in their teens and early twenties who also worked in factories to contribute to their families’ upkeep, needed an outlet. They longed for adventure, flirtations, and, perhaps, a bit of love. Their mothers, however, warned them that if they flitted around the neighborhood with immoral men, they could very well be “eternally disgraced by devil babies.”[25]

One young woman wrote Addams a letter about her fear of reproducing a Devil Baby. She was so afraid that someone would identify her from the information she included that she refused to sign her name to it. Her letter reveals the low literacy level that many of the people living near Hull House had, and it must have been difficult for Jane Addams to even understand the message. This anonymous author told Addams about the men who flirted with her and her friends on their way home from the tailor shop where they worked. The men were usually drinking beer and trying to tempt the girls to go to a dance hall with them. The girl wrote that one of her friends, “she say oh if you will go with them you will get devils baby like some other girls did who, we knows, she say Jane Addams she will show one like that in Hull House.”[26] Her story was enough to prevent her friends from further flirtation.

On a sadder note, some of the women who sought out the Devil Baby at Hull House came because they felt guilty that they had given birth to developmentally disabled or mentally ill children or those with physical disabilities. The Devil Baby became a symbol of what they saw as their own failures. Women whose children had become criminals also felt cursed by a devil in their midst. The presence of a supposed Devil Baby at Hull House brought up the memory of their own tragic lives. It also made them feel companionship with other mothers in similar situations.

The Devil Baby hysteria ended as abruptly as it had begun. The Chicago Examiner article seemed to take the wind out of its sail. People found no evidence of a Devil Baby or even a deformed baby born in the neighborhood. Within the blink of an eye, everything returned to normal, and the Devil Baby was forgotten. Jane Addams herself learned several lessons from the Devil Baby experience which stayed with her for the rest of her life. It changed the way she looked at aging and poverty, especially for women, and gave her insight into the world of tradition, myths, and the power of superstition.

Lessons Learned: How Researching Newspapers Can Add Depth to Understanding History

Jane Addams always kept her discussion of the Devil Baby within the confines of the Hull House neighborhood. Although her analysis reached across borders into the world of mythology, it did not consider other factors that could have sparked off the mania that autumn of 1913. In a situation like this, a historian who has the luxury of hindsight can offer new ideas to the discussion. In particular, newspapers are an excellent source for understanding the past. They are immediate, dramatic, and revealing.

In this case, I chose to zero on in one Chicago newspaper, The Chicago Tribune, a respected organ whose masthead read, “The World’s Greatest Newspaper.” Founded in 1847, the Tribune was known far and wide for its coverage of international, national, and local events. In 1910, its co-editors, the cousins Robert R. McCormick and Joseph Medill Patterson, took the newspaper to a broad audience by introducing advice columns, comic strips, cultural events and campaigns reflecting the spirit of the Progressive Era. At the end of March, 1913, the Tribune had a daily circulation of 243,449 and a Saturday circulation of 303,110. It also produced a Sunday edition of over one-hundred pages including a separate cartoon section and a magazine. I decided to concentrate on the Tribune rather than The Chicago Examiner because the latter was considered more sensational, and I wanted to have a more reliable source in terms of what was going on in Chicago and the wider world at the time of the Devil Baby incident.

I decided to go through entire issues of the newspaper dating from September 1 through November 8, 1913 with this primary question in my mind: What factors and events could have placed so much pressure on people’s lives that the existence of a Devil Baby seemed not only plausible but without a doubt, real, and very appealing? I looked closely at the approximately four weeks before the incident began and then continued for a week past its conclusion.

The first thing that struck me was that in mid-September, the Spiritualist Association of the U.S. had a major meeting in Chicago. The Tribune reported that during its sessions, twenty-five dead people wrote notes to those in attendance.[27] By its closing session on September 21, there had been evidence of all sorts of spirit manifestations, including tales from mediums of children having a special sensitivity to spiritualism. In one case, a child of four saw a “shadow” of her playmate who had just been buried.”[28] Although many of Chicago’s poor did not have the one cent to purchase the newspaper, those that could afford it or who found it in the trash shared the most titillating stores. News of spiritualists communing with the dead certainly fit the bill.

Of more consistent interest, however, was the weather and its interplay with living conditions and health. This may sound strange, but think about it for a moment. The population most deeply invested in the Devil Baby was poor. They lived in tenements, shacks, the rear apartments of small two and three-story houses, rooming houses, or, if need be, in temporary shelters or even on the streets and in parks. They rarely benefitted from heating in the winter, and they most certainly did not have air-conditioning or fans in the summer. Many did not yet have electricity. They often lived in crowded spaces where smells from summer sweat, unwashed bodies and clothing, and garbage from uncollected piles in the streets assaulted their olfactory nerves. The garbage situation was so bad that on October 9, crowds of “enraged citizens” protested at a garbage site because refuse had gone uncollected for eight days. As the Tribune reported, “At a conservative estimate, 4,000 tons are

lying in the cans and alleys of the city.”[29]

Winters in Chicago were often cruel, with bitterly cold winds coming off of Lake Michigan, extremely low temperatures, and plenty of snow. The poor people living around Hull House were lucky to have any heat in their apartments, most coming from small coal or wood burning stoves or fireplaces also used for cooking the meager meals they could afford. They could not afford fur-lined or insulated winter coats or boots for traversing through the icy streets. Rather, they piled on layers of thin clothes and shivered all night while huddled under thin blankets.

The poor living conditions certainly heightened people’s concerns about health, As “Mrs. Lee,” the head of the Housing Committee of Chicago’s

Women’s Club put it, “There are hundreds of children dying because of basement homes and we haven’t enough money to remedy the defects even in one small district.” [30] Today, we think nothing of going to a doctor or even to the Emergency Room if we are ill, but there was little money to spend on health care before the days of Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act. Poor people, especially the newly-arrived immigrants in Chicago, who did seek out physicians often fell victim to quacks who knew nothing about healing the ill but did know a great deal about bilking people out of the few dollars they had in their pockets. In late October, the Tribune started a campaign against these frauds. Begun on October 27, within a week, the effort had been adopted by the American Association of Foreign Language Newspapers and some U.S. officials. As S. R. Pietrowicz, M.D. wrote, “I have the records of a large number of cases where they (quacks) have not only robbed poor immigrants but have ruined their health.” He wanted these “human vultures” stopped and punished.[31]

Under these conditions, it is easy to understand the effect the weather could have had on the community’s psyche. Hot or cold, living a healthy and comfortable life was almost impossible. This said, the summer of 1913 was a doozy. On September 3, the Tribune reported that the day before was the hottest September 2 in the city’s memory. Temperatures reached 97 degrees at four in the afternoon. It was so hot that James McDonald, a laborer taking a break in Patrick Curtis’s Saloon at 515 South Halstead “dropped dead” and two children in the city also succumbed from the heat.[32] In addition, hundreds of “down and outs” from teens to old men, surged into Grant Park, seeking a comfortable place to sleep. They took up residence along paths and by the lake, causing trouble for themselves and for the police.[33] As the Health Department reported a few days later, the summer temperatures were on average 3.3 degrees higher than usual resulting in an increase in the death of babies under the age of one from heat and diarrhea and a total of seventy-one deaths from sunstroke during the months of June, July, and August.[34]

The one relief people could find was a concrete “bath tub” which had been constructed three years before. Located in West Park No. 2 (Stanford Park), the tub was part of a large recreation area created for a largely immigrant community consisting of “Russian, Jewish, Irish, Italian, Polish, Greek, and Lithuanian” residents. Folks could swim, shower, and bathe. More than 60,000 men and 30,000 women took advantage of the free showers during June and July alone. “West Park No. 2,” the Tribune reported, “stands for democracy, justice, good citizenship, neighborliness, brotherhood.”[35]

Not two weeks later, the temperatures dropped forty four degrees within fifty-nine hours and a cold Northeasterly wind blew in at twenty miles per hour.[36] For about three days, the temperature reminded people that winter was closing in on them. In fact, within a month, the city experienced its first snow storm of the season. That October 21st day brought in cold northwest winds of thirty miles per hour “of the blizzard variety.”[37] It remained cold for three or four days and then moderated a bit, but Chicagoans knew that it was going to be a long, cold winter. The fact that landlords chose arbitrarily when to send up heat, if a building had any, only added to the tension.[38]

During the long, cold winters that were so common in the Upper Midwest, life was very difficult, and tensions rose. For many poor families, it did not help that scores of men returned home from summers as itinerant farm and construction laborers only to be faced by unemployment. Henry M. Hyde, a progressive reformer and writer for the Tribune had a regular first page column he titled, “We Will.” On September 24, he addressed the question, “How Shall City Care for Jobless During Winter?” He calculated that the “army of casual laborers” then beginning to return to the city numbered about 25,000. With no wages and no work, they added to the hardships of the winter. He urged the city to do something about their situation.[39] Apparently, little was done. In fact, job loss even reached down to 112 children under the age of eighteen who in mid-October lost their positions in the schools. The Building and Grounds Committee of the Chicago school system decided that their work, often consisting of simply opening and closing windows and emptying waste baskets, put a drain on school appropriation funds.[40]

The weather was not the only cause for increased uncertainty about life. Fires were another reason to despair and to welcome any diversion offered, even in the guise of a Devil Baby. In August alone, Chicagoans experienced 703 fires.[41] As I journeyed through the articles which appeared daily, it became apparent that many of these incidents were caused by kerosene in the kitchens. Just a few examples will serve to illustrate the situation. On September 15, a twelve-year-old girl living in the West Side poured kerosene on burning fuel in the kitchen “range,” causing an explosion. Neighbors heard the poor girl’s screams and ran in to help her, but at the time of the article, there was doubt that she would survive.[42]

A week later, another young teenager, this one thirteen, died when her clothing caught fire from a flame from a small gas stove.[43] A month after that, on October 17, a mother and her seventeen-year-old daughter were cleaning rugs when a gas line exploded.[44] Their fates are unknown. In addition, there were a few major fires. On September 2, a fire on State Street burned for twelve hours, injuring forty-seven firemen.[45] On October 6, fourteen horses were burned to death in a fire at the Manhattan Bottling Works stable. Perhaps the work of an arsonist, it was the first of three blazes that day.[46] And on October 25, the paper reported that twenty workers were trapped by ammonia fumes at a fire in the stockyards on the West Side. A third of all of Chicago’s fire fighters were sent to the yards where weak water pressure hampered their efforts.[47] More burns. More grief. More death.

When looking through the Tribune, it became apparent that Chicagoans were very concerned about the safety of children, whether from the above-mentioned fires or unhealthy living conditions to the high number of automobile accidents. They lamented about deserted children, feared for those kidnapped and abused or those who wandered away. And, of course, they worried about those who strayed away from a moral life to one that threatened future degradation. Much of their dismay came from what they saw as a violent atmosphere in the city. As a September 1 article illustrated, people were appalled by a “Butcher Contest” held in Forest Park that was attended by over two thousand children. There they witnessed six steers roped and dragged onto a platform. The animals were tied up in a row, and then a “big man” walked down the line, clobbering each of the brutes on the head with a sledge hammer. Once the animals collapsed, another man took a knife and slit their throats; other men following along cut off their heads and feet. To top it all off, six more huge men skinned and cut them in half.[48]

Although street fights, gang shootings, and crimes of passion all added to the population’s stress, surprisingly, cars were even more of a danger than violent crimes. On October 3, the paper reported that there were 180 accidents in September alone.[49] Every day, new accidents were reported, but the paper often zeroed in on those that harmed children. For example, on September 13, a group of school children were mowed down by several autos. A number of mothers complained that the streets were unsafe because of the “recklessness of automobile drivers, motormen, and teamsters.” In one case, a group of children had been injured and two were near death.[50] Day after day, children were frightened, run-down, or harmed in some way by automobile and truck drivers.

More terrifying, however, was the number of children deserted, kidnapped, or simply lost for a while after they wandered away. The Tribune preferred stories about deserted children who had been shown some love. In the case of three-year-old Emily Mander, for example, the paper cheered on the couple who had decided to adopt her.[51] In another, more detailed article, the journalist told the story of a young woman who had fled the hospital a mere two hours after giving birth to a baby boy. This was at a time when women who could afford a hospital usually stayed there for at least a week after child birthing. In this case, said woman returned to the midwife at midnight, thrust some money into her hands, urged her to take good care of the baby, kissed the infant farewell, and then slipped away in an automobile.[52] This was obviously a woman with money, but also one who could not bear the shame of having given birth out of wedlock.

Also hopeful, but a bit disconcerting, were the articles reporting about children wandering away from home. These were not kidnapped children, just those, such as the two five year olds who were found crying several blocks away from home.[53] Or the two children, ages four and five, whose parents found them at the local police station.[54] More serious was the story of a thirty-year-old man who abducted a four-year-old girl, took her to a room, and “mistreated” her. Four hours later, she was found on the street crying.[55] The paper did not say what happened to the man, but it appears that he was apprehended. These three stories makes one wonder about the difficulty of keeping a constant eye on young children in the crowded, stifling atmosphere of an urban city at a time when there were no day-care centers or after-school programs.

Much concern was expressed about pre-teen and teenage children who used the streets as their playground. Gambling was a major topic of discussion in the newspaper. On September 1, the stories already reflected reform efforts to stop the “Dice Evil.” In this case, an investigation and raids were carried out at three saloons and three pool rooms on West Sixty-Third and South Halsted Streets in which twenty-six games of dice were alleged in each.[56] A week later, the paper reported that dice players lured children into their clutches with candy and then cigars. Then they further corrupted their victims with “200 different forms of petty gambling games carried on by means of cards. . . paddle wheels, dice and punch boards.” These games attracted girls as well as boys.[57] On September 11, seventy people were arrested in gambling raids, and the very next day, saloon owners united to fight for its members’ rights.[58]

Where gambling united the worries of the community was its encouragement of juvenile delinquency. Henry M. Hyde remarked in his “We Will” column of September 27 that the courts were not only full of cases against young boys but also of “hundreds” of girls and young women brought in each month for “sex” crimes. Most were immigrants. Parental neglect and poor education, he felt, caused most of their situations. Many of the girls could not speak English very well which is what probably led to their not going beyond the third grade.[59] To cope with long days in low-income jobs, these girls turned to barroom dances held every Saturday night. Along with dancing came liquor and along with liquor, sex.[60]

Certainly, alcohol abuse and gambling added to the stress of married women. On October 16, Henry Hyde posed the question, “Why did 2,500 men run away from their wives and families in Chicago last year?” The answer came from a report by the Court of Domestic Relations which stated that 75% of desertions were caused by “booze.” The document went on to explain that low wages, hard work, immorality, and drunkenness were predominant causes of desertion. However, interestingly, men were not the only ones to blame. Wives’ bad housekeeping, poor cooking, and nagging were also cited. Less frequent were husbands’ immorality, venereal disease, and domestic violence and the presence of mothers-in-law in the household. There was no simple black and white answer to Hyde’s question. Poverty, he indicated, lay at the bottom of it all.[61]

The women Jane Addams found most invested in the Devil Baby were elderly. Yet, the Tribune hardly concerned itself with them. As the women themselves knew, they were invisible. I found only three mentions and all had to do with falls of “aged” women in their sixties.[62]

You can see that there were a great many pressures for anybody living in the poor areas of Chicago, but immigrants appeared to have it especially hard. Besides the immediate conditions of their lives, there were also international events that could have added to their anxiety. Just in September and October alone, the Chicago Tribune reported on terrible riots in Dublin, Ireland, surrounding a Transport Workers’ Union strike. In addition, for no apparent reason, four houses collapsed in Dublin killing forty-four.[63]

Further east, there was a war in the Balkans lasting from June 29 to August 13 which had repercussions for a long time to come. This one included great atrocities including the burning of entire villages, beatings, the gouging out of eyes, and the rape and abduction of Bulgarian women. Letters confiscated from Greek soldiers and officers, later proved authentic, admitted to these. “We have burned all the villages abandoned by the Bulgarians,” one said. “They burned the Greek villages and we the Bulgarian villages. They massacre, we massacre, and the rifle has operated against every member of this dishonest nation who has fallen into our hands.”[64]

Immigrants probably did not get their news from the Tribune but rather from letters sent from back home in Europe or through the foreign-language press. They would have known of the growing tensions which eventually led to the outbreak of World War I in August, 1914—border disputes, ethnic tensions, anti-Semitism, over-crowding, famine, internal migrations, and a plethora of other causes. It is interesting, therefore, to note an article from the September 5 Tribune claiming, “Growing Insanity Among Alien Born Problem in City.” Henry Hyde featured the news in his column, using information from the weekly sessions of the Insane Court at the Detention Hospital. According to the data, which was broken down into more than thirty-five different national groups, the highest number of those institutionalized actually were labeled as “U.S.” (964). Next came German (266), Russians (183), Polish (160), Irish (147), Swedes (108) and a group designated simply by skin color, “Negroes” (104). Those with hardly any incidents of insanity included a wide diversity of people, some from Japan, Cuba, China, Mexico, Greece, Holland, Hungary, and France.

Hyde claimed that the problem was caused by the move from a rural area to an urban one, where people were “suddenly plunged down into the center of a whirlpool of noise, confusion, and excitement.” Skyscrapers, elevated trains, trolley cars, autos, and trucks, crowded sidewalks, unfriendly natives, and an assault of the English language caused “an unimagined monster.” Speaking only of men, the article then claimed that such a man became a drunk and then could not earn money to take care of his family. It was up to Chicagoans to “help by showing more sympathy in his dealings with the immigrants.”[65]

Finally, I thought it might be intriguing to look at how the Tribune covered Jane Addams and Hull House. There were only four articles which mentioned them during the ten weeks I surveyed, and none of them had to do with the Devil Baby. However, one of them, published on October 30, attracted my attention especially when I compared it with the October 31 article in the Chicago Examiner which appears near the beginning of this essay. If you recall, I noted that I chose to look closely at the Chicago Tribune because it had more integrity and was not seen as sensationalistic. But this piece gave me pause. Was it any less sensational than the piece in the Tribune? In fact, both treated Jane Addams most respectfully, but this one does seem to picture her as a bit naïve and vulnerable as it did so many of the poor, immigrant women. Food for thought.

The headline stated, “Annoys Jane Addams; Held.” The sub-heading carried a curiously scandalous tone: “Armed New Orleans Man Captured for Mailing Offensive Letters to Hull House Head.” The article read:

Henry Leunker, sought by the police on charges of annoying Miss Jane Addams by persistently writing love letters to her for two years, yesterday was arrested in New Orleans, according to a report from that city. His letters at first were appeals for help and as such were answered by Miss Addams. Later they became incoherent and contained offensive remarks. He was armed when arrested.[66]

Reading through a newspaper day after day as I did with the Chicago Tribune can give you a different look at history. It is both more intimate and yet broader. The next section suggests some ways that you can deepen your own analysis of the Devil Baby incident.

Lessons Put into Practice

- To understand an episode in history, historians look at other occurrences at the time to see if there might be a cause and effect relationship. In this case, I chose to survey all of the issues of The Chicago Tribune from September 1 through November 8, 1913. This was a narrow sample for a historian, but I simply wanted to give you an idea of what such an endeavor can reveal. Why don’t you choose another newspaper of the time—either international, national, or local—and see if you can find other occurrences that could have set off a Devil Baby incident. Use the same ten-week time frame, but choose only two or three different days for your experiment. Keep an open mind as to what you might find. Jot these things down. Does your reading confirm what I found or contradict it? Does it add anything new? (Here’s a little hint. I found all of the Chicago Tribune on line. You might use other newspapers’ digital archives or you can go to a library or historical society for more local periodicals.)

- The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 was the most dramatic “devil” episode in U.S. history. Do a bit of searching on the internet or in books to find out something about it. How did it start? What happened during it? How did it end? Then find out what theories historians, non-fiction writers, novelists, and playwrights have put forth for the hysteria that took place in Massachusetts. How have they differed in their interpretations? Were they influenced by psychological, cultural, gender, or class theories?

- There have been other Devil Baby sightings in U.S. history including one in the New Jersey Pine Barrens starting in the eighteenth century and continuing to today, another in Cleveland, Ohio, that took place in 1888, and another in Detroit, Michigan, in 1904.[67] I have a neighbor who in August, 2015, told me an interesting (and scary) story. She is Puerto Rican but was raised in an orphanage on Staten Island, New York, that was run by Catholic Nuns, many of them from Ireland. When I told her about the Devil Baby at Hull House, she immediately asked if the women who sought out the baby were from Europe. When I said yes, she told me about her own experience. The nuns who raised her told young girls in the orphanage not to go out into the woods. There was a green man there with a hatchet in his head. If he caught them, they could end up with a green baby with a hatchet in its head. Obviously, there are a number of myths and superstitions surrounding the Devil Baby. Speak with your friends, relatives, and neighbors and see if any of them have ever heard of a similar incident or myth. Think about how many different cultures have such tales. How are they similar? How are they different?

- Times may have changed, but older people still have a sense of being invisible in U.S. society. Look around your neighborhood. What is the situation for the elderly? Are there organizations, social service programs, or other outlets for them? Are they ignored or included in your world? If included, how? If ignored, what would you do to improve their situation?

Endnotes

Many thanks to Margaret Meacham, Anne Marie Pois, Victor Alonso, Gail Gurland, Laurin Grollman, Joseph Nagler, and Betsy Rorschach for their helpful comments on this piece.

[1] “‘Devil Child’ Still Sought by Thousands,” Chicago Examiner 11, no. 269 (October 31, 1913):5, col. 7. Mysterious Chicago Blog, www.mysteriouschicagoblog.com/2013/10/100-year-of-hull-house-devil-baby.html. Accessed August 7, 2015. I would like to thank Adam Selzer for his aid in citing this source.

[2] Jane Addams, “A Modern Devil-Baby,” American Journal of Sociology 20.1 (1914): 117-118. Jstor.org/stable/2762978. Accessed August 27, 2015.

[3] Jane Addams, “The Devil-Baby at Hull House,” The Atlantic Monthly CXVIII (October, 1916): 441-50. www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1916/10/the-devil-baby-at-hull-house/305428/. Accessed August 4, 2015; Jane Addams, The Long Road of Woman’s Memory (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1916; reprint, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002).

[4] Jane Addams, The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House, September 1909 to September 1919 (With a Record of a Growing World Consciousness) New York: The Macmillan Company, 1930.

[5] Addams, Second Twenty Years, p. 50. Addams always hyphenated Hull-House, but over the years, the hyphen was dropped. I have only used it when Addams did.

[6] Addams, “The Devil-Baby at Hull House,” The Atlantic, 441-50.

[7] All references in the imagined scenes are adapted from and quoted from Addams, The Long Road of Woman’s Memory. In this case, see page 8.

[8] Addams, The Long Road, p. 9.

[9] Ibid., p. 9.

[10] Ibid., p. 8.

[11] Addams, The Second Twenty Years, p. 66.

[12] Addams, The Long Road, p. 8.

[13] Addams, The Second Twenty Years, p. 53.

[14] Life expectancy for men in 1913 was 50.3 years. “Life Expectancy in the U.S.A., 1900-98. http://www.demog.berkeley.edu/~andrew/1918/figure2.html. Accessed August 7, 2015.

[15] Addams, The Long Road, p. 12.

[16] Ibid., p. 13.

[17] Ibid., p. 13.

[18] Ibid., p. 13.

[19] Ibid., p. 15.

[20] Ibid., p. 24.

[21] Addams, The Second Twenty Years, pp. 54-55.

[22] Addams, The Long Road, p. 11.

[23] Ibid., p. 18.

[24] Addams, The Second Twenty Years, p. 63.

[25] Addams, The Long Road, p. 20.

[26] Ibid. p. 20.

[27] “Spirits of Great Write to Earth,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 221C (September 15, 1913): 1, col. 4.

[28] “Mediums Tell of Childhood Spook,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 227C (September 22, 1913): 5, col. 1.

[29] “Enraged Citizens Raid Garbage Site After Big Meeting,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 242C (October 9, 1913): 1, col. 7.

[30] “Start to Solve Housing Problem,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 222C (September 16, 1913): 1, col. 4.

[31] “Foreign People Victims of Quacks,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 258C (October 28, 1913): 2, col. 3. Also see “Alien Press to War on Quackery,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 259C (October 29, 1913): 2, col. 5, and “War on Quacks Taken Up By U.S. Officials,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 260C (October 30, 1913): 1, col. 7.

[32] “Hottest September 2 in City’s Memory,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 211C (September 3, 1913): 3, col. 7. The newspaper was accessed through http://archives.chicagotribune.com from September 22 through October 5, 2015.

[33] “Forgotten Army, Hundreds Strong, Takes Grant Park,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 212C (September 4, 1913);1, col. 1.

[34] “Health Dept. Reports 3.3 Degrees Higher than Usual Temperatures Past Summer,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 36, Sunday Edition (September 7, 1913):6.

[35] “One Bath Tub To a Block But Oh! Such a Big Tub,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 38, Sunday Edition (September 21, 1913): Section 7, p. 64.

[36] “Chicago Shivers at Chill Blasts,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 227C (September 22, 1913):3, col. 1.

[37] “Chicago Shivers in First Snow Storm of Season,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 252C (October 21, 1913):1, col. 5.

[38] “Arbitrary Custom of Landlords in not Starting their Furnaces Before Some Time in October,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 39, Sunday Edition (September 28, 1913):Section V., p. 39.

[39] “How Shall City Care for Jobless During Winter?” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 229C (September 24, 1913):1, col. 1.

[40] “All School Employes (sic) Under 18 to be Ousted,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 244C (October 11, 1913): 11, col. 9.

[41] “Total Fires in August, 703,” Chicago Tribune LXXII no.218C (September 11, 1913): 17, col. 3.

[42] “Pours Kerosene on Fire: Girl May Die From Burns,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 221C (September 15, 1913):11, col. 1.

[43] “Burns Prove Fatal to Child,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no.38, Sunday Edition (September 21, 1913): 7, col. 4.

[44] “Mother & Daughter Battle Fire,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 249C (October 17, 1913):3, col. 1.

[45] “Twelve Hour Fire on State Street; 47 Firemen Hurt,” Chicago Tribune LXII, no 211C (September 3, 1913): 1, col. 7.

[46] “Man Dead in Suspicious Fire,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 239C (October 6, 1913):3, col. 2.

[47] “Twenty Trapped by Ammonia at Stockyards Fire,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 256C (October 25, 1913) 1, col. 3.

[48] “Children Watch Butcher Contest,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 209C (September 1, 1913):2, col. 4.

[49] “Motor Accidents in September,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 237C (October 3, 1913):13, col. 1.

[50] “Autos Run Down School Children: Two Near Death,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 220C (September 13, 1913):1, col. 3.

[51] “To Adopt Deserted Baby,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 222C (September 16, 1913): 3, col. 3.

[52] “Visits Babe Barefoot in Auto,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 224C (September 18, 1913): 2, col. 2.

[53] “Two Boys Wander from Home,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 249C (October 18, 1913): 8, col. 3.

[54] “Two Lost Children Found,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 42, Sunday Edition (October 19, 1913): 6, col. 1.

[55] “Kidnaps Four Year Old Girl,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 239C (October 6, 1913): 11, col. 2.

[56] “Englewood League Plans Test Cases Against Dice Evil,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 209C (September 1, 1913): 1, col. 7.

[57] “Dice Game Row Ends in Tragedy,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 215C (September 8, 1913): 3, col. 1.

[58] “Gambling Raids Catch Seventy,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 218C (September 11, 1913): 5, col. 4, and “Saloon Men Unite to Fight for ‘26’,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 219C (September 12, 1913): 3, col. 1.

[59] “Ignorance Fills Court of Morals with Delinquents,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no 232C (September 27, 1913): 1, col. 1.

[60] “Barroom Dances Menace Future of Immigrant Girls,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 238C (October 4, 1913): 13, col. 1.

[61] “Experts Differ Upon Causes of Wife Desertion,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 248C (October 16, 1913): 1, col. 1.

[62] “Fall Kills an Aged Woman,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 247C (October 15, 1913): 5, col. 4, “Woman Injured by Fall on Street,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 250C (October 18, 1913): 7, col. 1, and “Aged Woman Killed By Train,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 250C (October 18, 1913): 13, col. 2.

[63] “Dublin Streets Full of Rioters,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 209C (September 1, 1913): 1, col. 4, “Forty People Killed as Four Houses Collapsed,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 211C (September 3, 1913): 1, col. 7, (CHECK), “Parade in Dublin Turns Into Riot,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 227C (September 22, 1913): 1, col. 4.

[64] “Letters Allege Greek Cruelty,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 212C (September 4, 1913): 2, col. 7 and “Bare Atrocities of Balkan Wars,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 255C (October 24, 1913): 2, col. 4.

[65] “Growing Insanity Among Alien Born Problem in City,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 213C (September 5, 1913): 1, col. 1 and 8, col. 1.

[66] “Annoys Jane Addams; Held,” Chicago Tribune LXXII, no. 260C (October 30, 1913): 5, col. 2.

[67] See Adam Selzer, Devil Babies (Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications, 2012). This is an ebook.